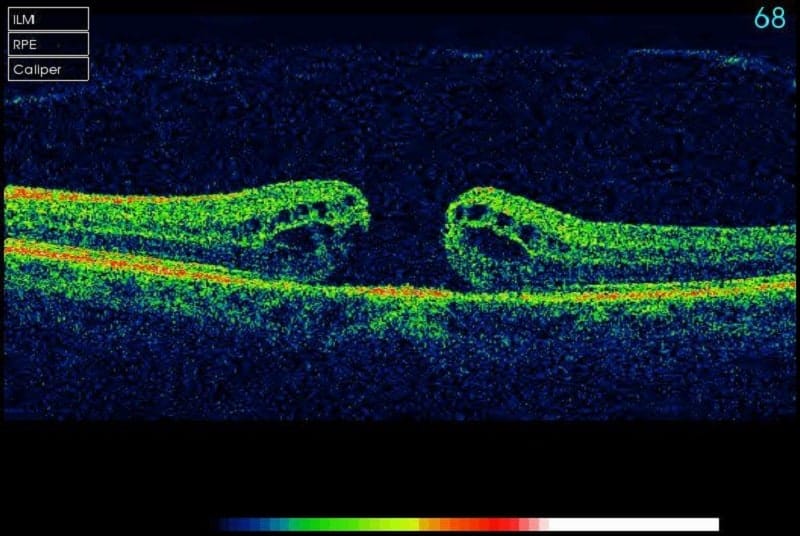

Macular Hole Introduction

A ‘full thickness macular hole’ is, as the name suggests, a hole that forms in the centre of the macula. The macula is the central part of the retina – the light-sensitive part of the eye like the photographic film in a camera. The macula serves your fine central vision, so when a macular hole develops, vision is reduced and distorted. The retina is very delicate nerve tissue, about one-third of a millimetre thick, and lines the inside of the back of the eye. Macular holes affect about 1 in 3000 adults per year, and because we are relatively symmetrical, if you get a macular hole in 1 eye, there is about 10% chance of developing one in your other eye too.

Causes

The vast majority of macular holes are caused when the vitreous (jelly) that fills the back of the eye pulls away from the retina at some point in your life. When we are young, the vitreous is like a solid ball, but it degenerates as we age and collapses in on itself at some point, pulling away from the retina. This is a normal ageing process that usually doesn’t cause any problems, but for some people, the vitreous is very firmly attached to the macula and can pull a piece off as it comes away, resulting in a hole. In a small proportion of cases, the macular hole can be caused by a severe injury, high myopia (short-sightedness), exposure to high-powered lasers, or sun-gazing.

Treatment

A ‘vitrectomy’ operation is performed to remove the vitreous using very small surgical instruments under an operating theatre microscope. This microsurgery is done via tiny incisions in the white of the eye that are smaller than a millimetre in size and often do not even need any stitches to keep them closed at the end of the procedure. Fine forceps (like tweezers) are then used to peel away the top layer of the retina which is quite elastic and tends to hold the hole open. Laser or cryotherapy (freezing treatment) may also be applied to treat other retinal problems in the periphery. The eye is then filled with a gas bubble that gradually goes away by itself and is replaced by the eye’s own natural fluid (‘aqueous’). The bubble makes the vision poor for up to 3 weeks and may be distracting in the meantime. Patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away (but can be driven). For large or persistent macular holes, a longer-acting gas bubble that takes up to 3 months to go away may be necessary, or even a silicone oil bubble. (Silicone oil needs further surgery to remove it but going to altitude is not a problem).

The surgeon cannot physically close the hole – we cannot glue it together or stitch it together – instead, the bubble does most of the work by squashing the edges of the hole back together. ‘Face down posturing’ – that is, looking down to the floor for much of the first week after surgery – increases the likelihood of repairing the hole, but only when the hole is large. Your surgeon will advise if posturing is recommended in your case. Standard posturing advice is face down for 50 minutes per hour for the first 5 days, and avoid sleeping on your back (termed ‘face up posture’) until the bubble is gone. It doesn’t matter what the body is doing while posturing, only what the eye is doing, so for that reason most patients find it easiest to sit at the dining table with their head rested on their folded arms or a pillow, rather than lying in bed. You can fill the time reading or using an iPad with the other eye. It is important to take a break from posturing every hour, and have normal upright posture during these breaks. Avoid the temptation to walk around looking at the floor as this will only give you a sore neck. Sleep on your side with either cheek to the pillow until the gas (or oil) is gone.

Timing of Surgery

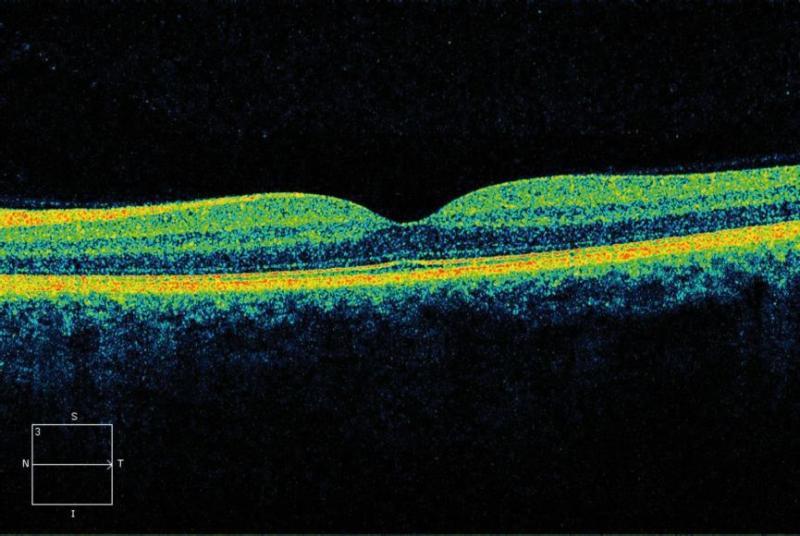

The timing of surgery is up to the patient. If the hole is very small, there is a small chance it may fix itself, so some patients prefer to wait a few weeks. However, for the vast majority, the hole keeps getting bigger and bigger over time, and the larger the hole is and the longer it has been there for, the poorer the chance of closing the hole and the poorer the vision is likely to be afterwards. As such, although this condition is not an emergency, best results are typically achieved with early surgery (i.e. within a month or so).

Benefits of Surgery

On average, we are able to close the hole in 90-95% of patients with a single operation. Providing we can close the hole, the vision will usually improve significantly but may not return to normal. Mild residual distortion is not uncommon. The vision tends to slowly continue to improve over months to even years. Any coexisting eye disease (such as macular degeneration, previous injury, retinal detachment, or high myopia [short-sightedness]) reduces the likelihood of visual improvement. As such, individual results vary and in some patients the vision fails to improve.

Risks

As with any operation, there are potential risks. In the vast majority of cases, the operation goes well and everyone is happy. About 1% of the time, the vision may be worse due to a long list of potential problems. There is a 1% risk of retinal detachment, where the retina peels away from the back of the eye like wallpaper coming off a wall – this is certainly vision-threatening and would require urgent surgery, but the vast majority can be repaired. There is about 1 in 2000 risk of blindness, usually from a nasty infection or bleed (‘haemorrhage’). And those who have not yet had cataract surgery can expect to develop a cataract within 6 or 12 months. Up to half of patients will have raised intraocular (eye) pressure within the first few weeks after surgery, which is monitored and treated as necessary but may rarely cause damage to the optic nerve (‘glaucoma’).

And a reminder that patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away. If additional surgery is planned within a few weeks of vitrectomy, the anaesthetist will need to know about the bubble in the eye as it may influence the gases they use for anaesthesia. A wrist band will be applied to alert them. The risks are low, but not zero – just like crossing a road!

Anaesthesia

The operation is usually performed under ‘local anaesthesia with sedation’, so patients are awake but given medicine to help them relax. Anaesthetic is applied around the eye to make it numb and the operation is usually very well tolerated. A sterile drape goes over the eye and the face, tented up so there is plenty of air coming in. Unless patients are particularly claustrophobic, they usually do very well with this approach, and it is safer than having ‘general anaesthesia’ (in which patients are put to sleep and a breathing tube inserted via the mouth). General anaesthesia can be arranged for those who need it.

Contact us to get help with any questions you may have, or support you may need.