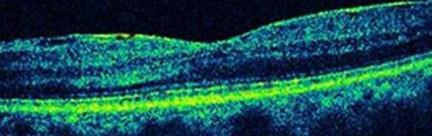

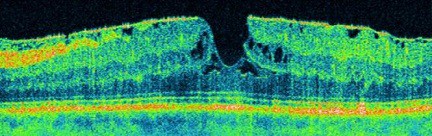

Epiretinal membrane Definition

An ‘epiretinal membrane‘ is a fine sheet of scar tissue on the surface of the retina, not unlike sticky tape. The retina is the light-sensitive part of the eye like the photographic film in a camera. It is very delicate nerve tissue, about one-third of a millimetre thick, and lines the inside of the back of the eye. Epiretinal membranes are surprisingly common (seen in around 7% of adults) and don’t necessarily affect the vision. If the membrane contracts (like old sticky tape), it distorts the retina resulting in reduced and distorted vision.

Causes

Most membranes occur for no known reason (what doctors call ‘idiopathic’), however the current theory is that most are an abnormal condensation of the jelly (‘vitreous’) that fills the back of the eye. Some membranes result from inflammatory debris or other cells released into the eye due to injury, retinal tears or detachment, blockage of blood vessels, diabetes, and other eye diseases.

Treatment

A ‘vitrectomy’ operation is performed to remove the vitreous using very small surgical instruments under an operating theatre microscope. This microsurgery is done via tiny incisions in the white of the eye that are smaller than a millimetre in size and often do not even need any stitches to keep them closed at the end of the procedure. Fine forceps (like tweezers) are then used to peel the membrane from the surface of the retina. Laser or cryotherapy (freezing treatment) may also be applied to treat other retinal problems in the periphery. The eye is then commonly filled with an air bubble that gradually goes away by itself and is replaced by the eye’s own natural fluid (‘aqueous’). This reduces the need for stitches and may further reduce the small risk of infection, however the bubble makes the vision poor for up to 10 days and may be distracting in the meantime. Patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away (but can be driven).

Timing of Surgery

The timing of surgery is up to the patient. If the symptoms are mild, the risks may outweigh the benefits, however delaying surgery until vision deteriorates may have a poorer final visual outcome.

Benefits of Surgery

On average, patients recover about half of the vision that has been lost due to the epiretinal membrane, and any distortion of the vision is usually substantially improved. However, the vision may be worse initially and improvement can take a few months. Any coexisting eye disease (such as macular degeneration, diabetes, previous injury or retinal detachment) reduces the likelihood of visual improvement. At the end of the day, all we can do is peel away the scar tissue and let nature take its course, so individual results vary and in some patients the vision fails to improve.

Risks

As with any operation, there are potential risks. In the vast majority of cases, the operation goes well and everyone is happy. About 1% of the time, the vision may be worse due to a long list of potential problems. There is a 1% risk of retinal detachment, where the retina peels away from the back of the eye like wallpaper coming off a wall – this is certainly vision-threatening and would require urgent surgery, but the vast majority can be repaired. There is about 1 in 2000 risk of blindness, usually from a nasty infection or bleed (‘haemorrhage’). And those who have not yet had cataract surgery can expect to develop a cataract within 6 or 12 months. Up to half of patients will have raised intraocular (eye) pressure within the first few weeks after surgery, which is monitored and treated as necessary but may rarely cause damage to the optic nerve (‘glaucoma’).

And a reminder that patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away. If additional surgery is planned within a few weeks of vitrectomy, the anaesthetist will need to know about the bubble in the eye as it may influence the gases they use for anaesthesia.

The risks are low, but not zero – just like crossing a road, driving a car, or getting on an aeroplane!

Anaesthesia

The operation is usually performed under ‘local anaesthesia with sedation’, so patients are awake but given medicine to help them relax. Anaesthetic is applied around the eye to make it numb and the operation is usually very well tolerated. A sterile drape goes over the eye and the face, tented up so there is plenty of air coming in. Unless patients are particularly claustrophobic, they usually do very well with this approach, and it is safer than having ‘general anaesthesia’ (in which patients are put to sleep and a breathing tube inserted via the mouth). General anaesthesia can be arranged for those who need it.

Contact us to get help with any questions you may have, or support you may need.