Retinal Detachment Definition

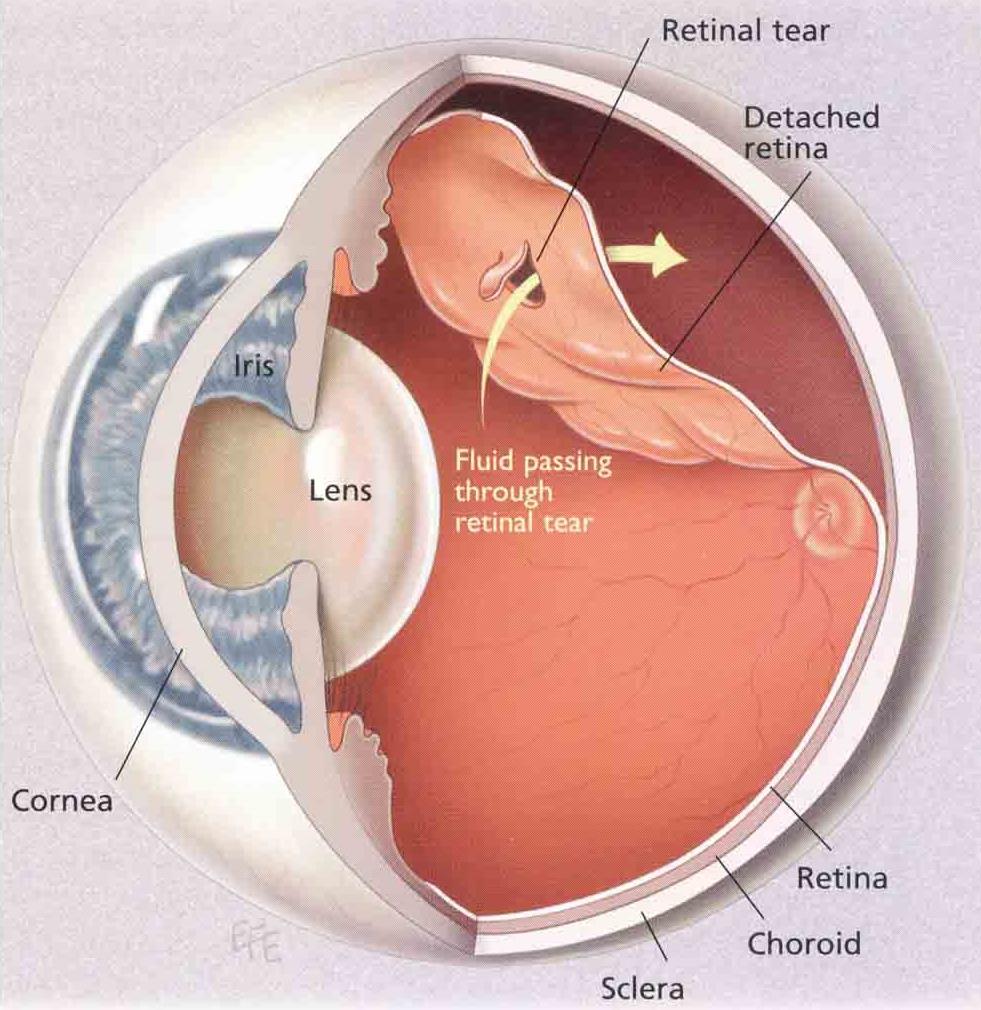

The retina is very delicate nerve tissue like photographic film in a camera that lines the back of the eye. Retinal detachment occurs when the retina peels away from the inside of the eye like wallpaper coming off a wall. Retinal detachment occurs in about 1 in 10,000 people per year, but if one eye is affected, there is about 10% chance of developing the same problem in the fellow eye at some stage.

The macula is the central part of the retina which serves your fine central vision, and whether the macula has been affected by the retinal detachment or not (described as ‘macula on’ or ‘macula off’ retinal detachment) will help determine the urgency of surgery and the likelihood of the vision improving afterwards

Causes{“type”:”block”,”srcClientIds”:[“4b3b7981-9a94-4a73-8b68-a159f1e39c73″],”srcRootClientId”:””}

The vast majority of retinal detachments occur when the vitreous (jelly) that fills the back of the eye pulls away from the retina.When we are young, the vitreous is like a solid ball, but as we get older it gets more watery and collapses in on itself at some point, pulling away from the retina. This is a normal ageing process that usually doesn’t cause any problems, but in some people the vitreous is very firmly attached to the retina and can cause holes and tears as it comes away. This can allow the watery vitreous to seep through the breaks, resulting in retinal detachment.

High myopia (short-sightedness) and lattice degeneration (an abnormal attachment between the vitreous and retina) increase the risk of retinal detachment. Trauma (injury) accounts for only a small proportion of cases.[vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”5845″ img_size=”full” css=”.vc_custom_1587698569383{padding-top: 53px !important;}”](In rare instances, the retina can detach without a hole present due to fluid accumulating under the retina – these unusual cases are not the subject of this discussion).[vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1587698766606{padding-top: 20px !important;}”]Treatment

Most cases will require ‘vitrectomy’ surgery which is essentially ‘keyhole’ microsurgery. This is where the vitreous jelly is removed from the eye using very small surgical instruments under a special microscope in an operating theatre. This is achieved through tiny incisions in the white of the eye that are smaller than a millimetre in size and often do not even need any stitches to keep them closed at the end of the procedure. Laser or cryotherapy is applied to seal the retinal breaks, and because this treatment takes a week or so to work, we fill the eye with a gas bubble to keep the retina flat while it heals. The gas bubble slowly goes away by itself and is replaced by the eye’s own natural fluid called ‘aqueous’. The bubble makes the vision poor for 2 or 3 weeks and may be distracting in the meantime. Patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away (but can be driven). In some cases, a longer-acting gas bubble that takes up to 3 months to go away may be necessary, or even a silicone oil bubble. (Silicone oil needs further surgery to remove it, but going to altitude is not a problem with oil in the eye). Gas bubbles float (obviously), but since your vision is actually inverted (‘upside-down’), it will appear to you as though the bubble is slowly sinking down like a setting sun. In other words, the vision should start to improve from the top down.

Straight after the operation, most patients will be rolled over to posture “face down” for a number of hours to use the bubble to iron out the wrinkles in the retina and minimise the chance of having permanently distorted vision afterwards. Some patients will be given further posturing instructions for the first week or so after surgery. All patients should avoid sleeping on their back (termed “face up” posture) while the bubble remains in the eye, because for some people that will cause high pressure which could damage the nerve at the back of the eye. It is best to sleep on your side with your cheek to the pillow until the gas (or oil) has gone. We may specify which side to sleep on.

A small proportion of retinal detachments are{“type”:”block”,”srcClientIds”:[“4b3b7981-9a94-4a73-8b68-a159f1e39c73″],”srcRootClientId”:””} best managed with an alternative style of retinal detachment repair called a ‘cryo-buckle’ procedure. ‘Cryotherapy’ involves using a freezing probe to seal around the retinal breaks, and a ‘buckle’ (a piece of silicone like transparent rubber band) is stitched to the white part of the eye (‘sclera’) to push the wall of the eye back in contact with the retina. Occasionally, both ‘vitrectomy and buckle’ will be needed. Although the buckle is designed to remain in place forever, about 10% of patients will end up needing it removed at some stage. If you ever feel like you have conjunctivitis in an eye with a buckle, see your vitreoretinal surgeon for assessment. Some degree of double vision is not uncommon within the first 2 weeks after a buckle procedure, but rare thereafter.

Timing of Surgery

The urgency of surgery depends on a number of factors. Ideally, we fix the retinal detachment before the macula comes away as most of those patients will recover essentially normal vision afterwards. As such, fresh ‘macula on’ retinal detachments typically require surgery within a day or two. Once the macula has detached (‘macula off’), there is more of a question mark over what the vision might be afterwards, and studies show the results are much the same if it is repaired any time in the next week or 10 days. Some patients present with long-standing retinal detachments. These cases are less urgent, and occasionally conservative management (ie. leaving it alone) may be warranted. Your doctor will make recommendations based on your particular case.

Benefits of Surgery

Left alone, retinal detachment is typically a blinding condition. Retinal detachment surgery is successful in reattaching the retina in over 90% of cases with a single operation. That means for about 1 in 10 patients the retina will re-detach, and unfortunately they just keep getting harder and harder to fix. Ultimately, we are able to reattach about 99% with further procedures. So, although we can help most people, we cannot help everyone.

Those with macula off retinal detachments may initially have reduced and distorted vision despite surgery, but the vision will often slowly improve over weeks to months. In some patients, particularly those with long-standing retinal detachments, the vision fails to improve.

Risks

In the vast majority of cases, the operation goes well and everyone is happy. But as with any procedure, there are potential risks. The risks are low and most patients will go blind without intervention so this needs to be kept in perspective. There is about 1% chance that the retina cannot be reattached, even after a number of operations. This is almost always due to retinal scarring which is the body’s attempt to heal itself. Scars contract which can pull the retina away from the wall of the eye again, undoing our good work. There is also about 1 in 1000 chance of developing a nasty infection or bleed (‘haemorrhage’). And those who have not yet had cataract surgery can expect to develop a cataract within 6 or 12 months, which requires further surgery. Up to half of patients will have raised intraocular (eye) pressure within the first few weeks after surgery, which is monitored and treated as necessary but may rarely cause damage to the optic nerve (‘glaucoma’). In addition, there is a very small chance of a problem called sympathetic ophthalmia (about 1 in 14,000) where operating on one eye can affect the vision in both eyes. And a reminder that patients are unable to fly or drive or go to altitude until the bubble goes away. If additional surgery is planned within a few weeks of vitrectomy, the anaesthetist will need to know about the gas bubble in the eye as it may influence the gases they use for anaesthesia. A wrist band will be applied to alert them.

Anaesthesia

The operation is usually performed under ‘local anaesthesia with sedation’, so patients are awake but given medicine to help them relax. Anaesthetic is applied around the eye to make it numb and the operation is usually very well tolerated. A sterile drape goes over the eye and the face, tented up so there is plenty of air coming in. Unless patients are particularly claustrophobic, they usually do very well with this approach, and it is safer than having ‘general anaesthesia’ (in which patients are put to sleep and a breathing tube inserted via the mouth). General anaesthesia can be arranged for those who need it.

Contact us to get help with any questions you may have, or support you may need.